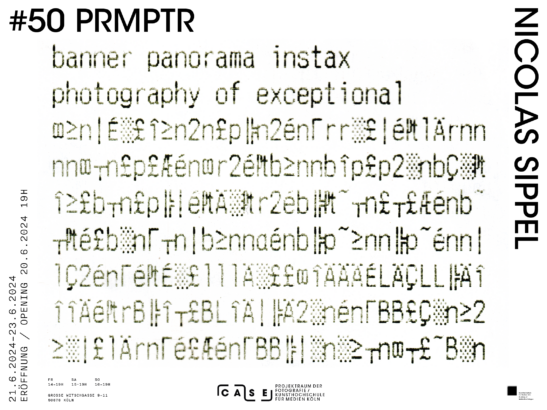

PRMPTR

1953 veröffentlichte der berühmte Autor Roald Dahl seine Erzählung vom »großen automatischen Grammatisator«.

Die dystopische Satire erzählt von einer Maschine, die auf Knopfdruck Geschichten produziert.

Ihr Erfinder Adolph Knipe, ein begabter Ingenieur und erfolgloser Schriftsteller, benutzt sie, um den Literaturbetrieb mit billiger und durchschnittlicher Lektüre zu überfluten und schließlich ein Monopol zu erlangen.

Dass diese Maschine auf den Werken anderer Autoren basiert und schlicht Stile und Narrative reproduziert, wird hier nur beiläufig erwähnt.

Diese damals wahnwitzige Idee ist heute so alltäglich, dass künstliche Intelligenzen in Schulen, Universitäten, am Arbeitsplatz, im Film und in der Werbung längst die kreativen Prozesse mitgestalten.

Dabei sind sie, ebenso wie Knipes’ Erfindung, zu originellen Inspirationen unfähig.

Beide bedienen sich an dem bereits Formulierten, an dem bereits Gedachten.

Neue Gedanken und Perspektiven ersticken in der Masse von mehr als 2000 Jahren Kulturgeschichte des Westens, welche die grundlegenden Datensätze der KI’s zementiert.

Das führt dazu, dass Fehlschlüsse und Stereotypen sowie systemische Diskriminierung, Ängste und Hass mit statistischer Wahrscheinlichkeit und mathematischer Genauigkeit reproduziert werden.

Ganz im Gegenteil sind Bilder durch künstliche Intelligenzen einer Transformation unterworfen.

Nachdem die Malerei durch die Fotografie von ihrem Abbildungsanspruch befreit wurde und diese wiederum durch die digitale Fotografie, so befreit uns KI endgültig von der Realität.

An die Stelle einer vermeintlich abgebildeten Welt treten prozedurale Wahrscheinlichkeiten, die aus den etlichen eingespeisten und verschlagworteten Bildern in kaskadierenden Berechnungen die Texteingabe der User*innen projizieren.

Prmptr befreit uns nun auch davon.

Prmptr bedient sich aller Substantive und Adjektive, wie sie im Oxford English Dictionary zusammengetragen wurden.

English:

In 1953, the famous author Roald Dahl published his story of the »Great Automatic Grammatizator«.

The dystopian satire tells the story of a machine that produces stories at the touch of a button.

Its inventor, Adolph Knipe, a talented engineer and unsuccessful writer, uses it to flood the literary world with cheap and mediocre reading material, eventually gaining a monopoly.

The fact that this machine is based on the works of other authors and simply reproduces styles and narratives is only mentioned here in passing.

This idea, which was ludicrous at the time, is now so commonplace that artificial intelligence has long since helped shape creative processes in schools, universities, the workplace, film and advertising.

However, just like Knipes’ invention, they are incapable of original inspiration.

Both make use of what has already been formulated, what has already been thought.

New thoughts and perspectives are suffocated in the mass of more than 2000 years of Western cultural history, which cements the basic data sets of the AIs.

As a result, false conclusions and stereotypes as well as systemic discrimination, fears and hatred are reproduced with statistical probability and mathematical accuracy.

On the contrary, with artificial intelligence, images are subjected to a transformation.

After painting was freed from its claim to depiction by photography, which in turn was freed by digital photography, AI is ultimately freeing us from reality.

A supposedly depicted world is being replaced by procedural probabilities of the numerous indexed images, projecting the user’s text input in cascading calculations.

Prmptr now liberates us from this too.

Prmptr uses all nouns and adjectives as compiled in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Prmptr knows no meanings or contexts and generates unique images for text-to-image AI at the push of a button.